1. The New World (Terrence Malick, United States)

Though it initially alluded this writer, as it seems to have many, The New World represents another major work by America's most singular latter-day auteur. (Perhaps the 135 min. re-cut helped my belated appreciation.) Malick's poetic idiom is perfectly suited to this presentation of the first contact between English settlers and Virginia area "naturals," with the absence of experiential precedence articulated on both sides. As with Badlands (1973), The New World marks a truly moving expression of a first, under-age love; as with Days of Heaven (1978) this is landscape filmmaking at its very best, thanks to a series of 'golden hour' compositions; and as with The Thin Red Line (1998), Malick's subjective voice-over shifts between multiple protagonists. History will decide if the hyper-romantic The New World is their equal, but clearly it is quite close indeed.

2. A History of Violence (David Cronenberg, United States)

2. A History of Violence (David Cronenberg, United States)No other contemporary Anglo director has as fastidiously examined the mysterious depths of human personality as has Canadian master David Cronenberg -- which certainly becomes all the more startling when once considers his propensity to engage psychological extremum. A History of Violence is no exception to this rule, even if it represents his most universal applicability: we have in this tale of salt-of-the-earth everyman Tom -- or is it Joey? -- a genuine inquiry into the nature of the human self that is singular in the contemporary cinema, let alone unique in Hollywood. To be sure, Cronenberg does address the more politically-seductive topic inherent in his title -- the nature of violence and our capacity to enjoy it is depiction -- but his conclusions may not warm everyone to whom a film like this would seem to speak: violence, he supposes, is inextricably within us (the impulses of Tom's son confer the very universality that Cronenberg's human curios often tend to mitigate). Yet in praising the ambitions of his message, it is important not to overlook the elegance of his very classical technique, which nevertheless he is quick to refashion when his narrative would seem to dictate that he do so -- as with the film's masterful opening sequence. A History of Violence is by quite a large margin the best English language release of 2005.

3. The Sun (Aleksandr Sokurov, Russia / France / Italy / Switzerland)

3. The Sun (Aleksandr Sokurov, Russia / France / Italy / Switzerland)

Russian maestro Aleksandr Sokurov's The Sun (Solntse) looks and feels like nothing else released during the past year, which of course could be said of any of the director's films. Then again, there is a particular bizarreness to The Sun's texture that reflects the film's alchemic combination of Sokurov's long-held preoccupations -- the mortal fate of a dictator, the passing of an imperial culture, Japanese aesthetics -- with a filmmaking technique that favors long takes, transgressions of the 180 degree rule, largely unaccountable manipulations of the visual track and a collection of sounds that trades heavily on the eerie and menacing. Likewise, the film's subject, Emperor Hirohito on the occasion of his renunciation of divinity following his nation's defeat, offers a splendidly mystical container for the Russian's favored examinations of the permeable boundary between life and death. All of this is to say that The Sun functions as something of a signature, revealing the vast sea of the director's aesthetic in a single, mesmerizing work.

4. The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (Cristi Puiu, Romania)

4. The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (Cristi Puiu, Romania)Cristi Puiu's second feature, The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, reaches the upper-most of artistic stratas on the basis of its rigorous formal conveyance of content: long takes inscribe the indifference of Dante Lazarescu's physicians and tower block neighbors as they sluggishly aid the infirmed widower; on occasion, Lazarescu actually disappears from the frame, problematically, as his helpers persist about their business without even a hint of urgency -- while that is time continues to pass unabated. This assures that the film's prolonged duration confers not only a feeling of exacerbation -- equal to that of Dante's paramedic companion -- but further, that it determines the inevitability of the protagonist's expiration. Whether it comments purely on Romanian mores or serves instead as a broader statement on the human condition, the director displays a coherent philosophy in his inverted ER -- after all, even Lazarescu's mangy cats lie around unmoved by his plight. That Puiu imbues such minor details with discursive significance confirms his artistic stature, as does his masterful use of color: he invents separate swatches for each of the five Bucharest emergency rooms that Dante tours, harmoniously composing the spaces in these varied hues. In this way, Puiu's previous vocation, painting, adorns what is otherwise a profoundly cinematic work.

5. Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taiwan)

5. Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taiwan)By a matter of degree, Hou Hsiao-hesien's finest since the 1990s -- though by no means the equal of his sublime Flowers of Shanghai (1998) -- Three Times is also the ultimate stretch for the Taiwanese master: a genuine crowd-pleaser. Even so, the director is not exactly new to gratifying diversions (A Summer at Grandpa's [1984] falls neatly within this category) nor is Three Times a visceral pleasure in the Hollywood blockbuster mode. Rather, it is that which might be best classified as cerebral entertainment, made accessible by a structure that provides the spectator easy critical entry. To this end, Three Times is constructed in three segments, all featuring the same couple in separate variations on the same love story. Situated in the 1960s, the first mines territory similar to his supreme The Time to Live and the Time to Die (1985), though its closest precursor would seem to be Wong Kar-wai's Days of Being Wild (1991) -- with Hou casting a spell no less than his esteemed colleague. The second, set in the 1910s, references Flowers of Shanghai, replete with the silent technique (and intertitles) that that film appropriate lacks. And the neon-saturated third part, returning to a post-modern world where sex can be shown on-screen, seems to suggest the near future of Millennium Mambo (2001). These riffs on Hou classics suggests nothing so much as a 'best of' compendium, constructing film in a manner commensurate with pop music -- even as its disparate structure seems aware of the reality of DVD connoiseurship.

6. Caché (Michael Haneke, France / Austria / Germany / Italy)

6. Caché (Michael Haneke, France / Austria / Germany / Italy)

No 2005 release benefited more from the chaos in Paris' suburbs than Michael Haneke's Caché, an astute divination of the wages of French complicity in producing a permanent underclass of racially-other North Africans. To be sure, this is subtext -- but of such substantial and timely insight that it cannot help but confer upon the film a degree of brilliance. The ostensible focus of Caché is the manipulation of subject by an invisible contriver: not exactly a new topic for Haneke. Yet, from its Benny's Video surveillance conceit, Caché extends into new territory for the director -- namely, footage of the impossible, of a distant past and of the internal -- suggesting that it may just be Haneke himself whom we are to regard as the originator of the video tapes that the protagonist couple receive. This is to say that Caché allegorizes Haneke's relationship to his medium, which is particularly evident in the filmmaker's refusal to distinguish the surveillance footage from present-tense depictions. Indeed, given Haneke's complex interweaving of these distinct narrative modes, Caché is that moment when maturity becomes mastery.

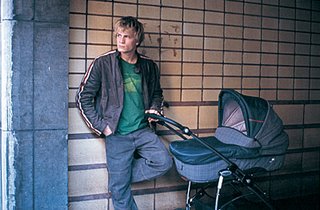

7. L'Enfant (Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne, Belgium / France)

7. L'Enfant (Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne, Belgium / France)Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne's L'Enfant (The Child), the Belgian brothers' second Cannes Palme d'Or winner, inverts the calculus of their previous masterwork, The Son (2002), to showcase the life of the sinner rather than the saint -- leading the pair into somewhat messier terrain narratologically. As with this earlier stunner, the sin committed veers toward the unforgivable: here, a new father -- the titular "child," in actuality -- sells his infant son for profit, leaving the boy's out-of-wedlock, teenage mother virtually catatonic. Presumably stricken by the workings of conscience, the young man seeks to right this transgression, only to lapse once again through a characteristic expression of his operative egoism (or in the parlence of the film, his childishness). Surely, the Dardenne brothers' exacting description of play likewise extends the analogy and recommends the film on another level -- the truth of its observations. Indeed, it is in such near-wordless passages that L'Enfant discloses its true genre -- the action film -- where the works enacting by the allegorical cipher lead him unevenly toward a Bressonian grace.

8. Oxhide (Liu Jiayin, China)

It is Liu's emphasis on off-camera space, procured through an exceptional reduction of the on-camera visual field that foremost marks Oxhide's contribution to contemporary minimalist art film practice. Considered as an aesthetic intervention, Liu's strategies shift the core of realist filmmaking from unaltered visual reproduction to the registration and indeed creation of space through primarily auditory means. At the same time, Liu's Oxhide methods no less indicate a filmmaker who has invented a style out of practical necessity: namely, that in shifting the emphasis from the visual to the auditory by means of reducing the scope of what is seen and what is brought into view through the film's exclusive use of a very limited natural lighting, Liu in effect masks the poverty of her micro-budgeted production. Oxhide's exceedingly restricted frame accordingly proves a polyvalent metaphor for the film's - and Liu clan's - comparable modesty. Oxhide indeed offers a template for the creation of comparably viable work under the most profound of restrictions.

9. Regular Lovers (Philippe Garrel, France)

"Winner of the of the coveted Louis Delluc Prize for Best French Film and the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 2005 Venice International Film Festival, art-house breakthrough Regular Lovers introduced the under-the-radar auteur, Philippe Garrel , to a new generation of cinephiles. Set in Paris in 1968 and 1969, the film follows twenty-year-old François—played by the director’s son, Louis Garrel—a poet, draft-dodger, and would-be revolutionary who falls in love with Lilie, a beautiful young sculptor. Drifting aimlessly between parties, protests and philosophical conversations, François and Lilie attempt to keep their romance intact as their ideals and ambitions pull them it different directions. A stylized, contemplative response to Bernardo Bertolucci’s ostentatious youth-culture reverie, The Dreamers, Garrel’s autobiographical long-take epic effortlessly captures the exhilaration, anxiety, and boredom of coming-of-age in a time of radical uncertainty." (Lisa K. Broad)

10. Linda Linda Linda (Nobuhiro Yamashita, Japan)

Nobuhiro Yamashita's Linda Linda Linda begins by asking whether one loses part of their personality when one becomes an adult. Yamashita's film proceeds to involve these same spectators in its high school narrative, which ultimately concludes with a performance of the titular song during a high school assembly (by a a trio of Japanese students and their Korean foreign exchange student front-woman). Following this penultimate sequence, Yamashita films a series of empty corridors and classrooms, thereby reminding the older spectator what he or she has lost. At this moment, Linda Linda Linda becomes Fast Times at Ridgemont High meets L'Eclisse. However, lest this makes Yamashita's picture sound anything but pleasurable, Linda Linda Linda operates on the basis of the Blue Heart's post-punk classic, achieving the same effect narratively as its rousing chorus. The universal Linda Linda Linda is one of the most purely entertaining films of 2005.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment